- Case StudyHelp.com

- Sample Questions

Aromatic Chemicals PLC: The Liverpool Project Assignment Solutions

Assignment Detail:-

- Number of Words: 3500

Are you seeking Aromatic Chemicals PLC: The Liverpool Project Assignment Answers? Casestudyhelp.com provides quality assignment help services. We have professional writers who assist you with assignment writing services at an affordable price. Students can also avail of our Assignment Help Liverpool by UK experts. Contact our 24/7 live chat member. We are happy to assist you.

Aromatic Chemicals plc: The Liverpool Project

Late one afternoon in January 2022, Robert Brown told Laura White, “No one seems satisfied with the analysis so far, but the suggested changes could kill the project. If solid projects like this can’t swim past the corporate piranhas, the company will never modernise.” Laura was plant manager of Aromatic Chemicals’ Liverpool Works in Liverpool, England. Her controller, Robert Brown, was discussing a capital project that Laura wanted to propose to senior management. The project consisted of a (British pounds) £300-million expenditure to renovate and rationalise the polypropylene production line at the Liverpool plant in order to make up for deferred maintenance and to exploit opportunities to achieve increased production efficiency.

Aromatic Chemicals was under pressure from investors to improve its financial performance because of both the worldwide economic slowdown and the accumulation of the firm’s common shares by a well-known corporate raider, William Bones. Earnings per share had fallen to 30.00 pence at the end of 2021 from around 60.00 pence at the end of 2020. Laura thus: believed that the time was ripe to obtain funding from corporate headquarters for a modernisation program for the Liverpool Works-at least she had believed so until Robert presented her with several questions that had only recently surfaced.

Aromatic Chemicals and Polypropylene

Aromatic Chemicals, a major competitor in the worldwide chemicals industry, was a leading producer of polypropylene, a polymer used in an extremely wide variety of products {ranging from medical products to packaging film, carpet fibres, and automobile components) and known for its strength and malleability. Polypropylene was essentially priced as a commodity. The production of polypropylene pellets at Liverpool began with propylene, a refined gas received in tank cars. Propylene was purchased from four refineries in England that produced it in the course of refining crude oil into petrol. In the first stage of the production process, polymerisation, the propylene gas was combined with a diluent (or solvent) in a large pressure vessel. In a catalytic reaction, the polypropylene precipitated to the bottom of the tank and was then concentrated in a centrifuge.

The second stage of the production process compounded the basic polypropylene with stabilisers, modifiers, fillers, and pigments to achieve the desired attributes for a particular customer. The finished plastic was extruded into pellets for shipment to the customer. The Liverpool production process was old, semi continuous at best, and, therefore, higher in labour content than its competitors’ newer plants. The Liverpool plant was constructed in 1990.

Aromatic Chemicals produced polypropylene at Liverpool and in Rotterdam, Holland. The two plants were of identical scale, age, and design. The managers of both plants reported to Ronald Gibs, executive vice president and manager of the Intermediate Chemicals Group (ICG) of Aromatic Chemicals. The company positioned itself as a supplier to customers in Europe and the Middle East. The strategic- analysis staff estimated that, in addition to numerous small producers, seven major competitors manufactured polypropylene in Aromatic Chemicals’ market region. Their plants operated at various cost levels. Exhibit 1 presents a comparison of plant sizes and indexed costs.

Do you want to get free assignment samples with examples by professional academic writers

The Proposed Capital Programme

Laura had assumed responsibility for the Liverpool Works only 12 months previously, following a rapid rise from the entry position of shift engineer nine years before. When she assumed responsibility, she undertook a detailed review of the operations and discovered significant opportunities for improvement

in polypropylene production. Some of those opportunities stemmed from the deferral of maintenance over the preceding five years. In an effort to enhance the operating results of the Works, the previous manager had limited capital expenditures to only the most essential. Now, what previously had been routine and deferrable was becoming essential. Other opportunities stemmed from correcting the antiquated plant design in ways that would save energy and improve the process flow: (1) relocating and modernising tank-car unloading areas, which would enable the process flow to be streamlined; (2) refurbishing the polymerisation tank to achieve higher pressures and thus greater throughput; and (3) renovating the compounding plant to increase extrusion throughput and obtain energy savings.

Laura proposed an expenditure of £300million on this program. The entire polymerisation line would need to be shut down for 48 days, however, and because the Rotterdam plant was operating near capacity, Liverpool’s customers would buy from competitors. Robert believed the loss of customers would not be permanent. The benefits would be a lower energy requirement as well as a 6 percent greater manufacturing throughput. In addition, the project was expected to improve gross margin (before depreciation and energy savings) from 11 percent to 12 percent. The engineering group at Liverpool was highly confident that the efficiencies would be realised. Robert characterised the energy savings as a percentage of sales and assumed that the savings would be equal to 1.2 percent of sales in the first 5 years, 0.7 percent in years 6-10 and 0.2 percent in years11-15. He believed that the decision to make further environmentally oriented investments was a separate choice (and one that should be made much later) and. therefore, that to include such benefits (of a presumably later investment decision) in the project being considered today would be inappropriate.

Liverpool currently produced 3,500,000 metric tons of polypropylene pellets a year. Currently, the price of polypropylene averaged £1300 per ton for Aromatic Chemicals’ product mix. The tax rate required in capital-expenditure analyses was 25 percent. Robert discovered that any plant facilities to be replaced had been completely depreciated. New assets could be depreciated on an accelerated basis over 15 years, the expected life of the assets. The increased throughput would necessitate a one-time increase of work-in-process inventory equal in value to 4.0 percent of cost of goods. Robert included in the first year of his forecast preliminary engineering costs of £16,000,000, which had been spent over the preceding nine months on efficiency and design studies of the renovation. Finally, the corporate manual stipulated that overhead costs be reflected in project analyses at the rate of 4 percent times the book value of assets acquired in the project per year.

The company’s capital-expenditure manual suggested the use of double-declining-balance (DDB) depreciation, even though other more aggressive procedures might be permitted by the tax code. The reason for this policy was to discourage jockeying for corporate approvals based on tax provisions that could apply differently for different projects and divisions. Prior to senior-management’s approval, the controller’s staff would present an independent analysis of special tax effects that might apply. Division managers, however, were discouraged from relying heavily on those effects. In applying the DDB approach to a 15-year project, the formula for accelerated depreciation was used for the first 10 years, after which depreciation was calculated on a straight-line basis. This conversion to straight line was commonly done so that the asset would depreciate fully within its economic life.

The corporate-policy manual stated that new projects should be able to sustain a reasonable proportion of corporate overhead expense. Projects that were so marginal as to be unable to sustain those expenses and also meet the other criteria of investment attractiveness should not be undertaken. Thus, all new capital projects should reflect an annual pre-tax charge amounting to 4 percent of the value of the initial asset investment for the project.

Robert had produced the discounted-cash-flow (DCF) summary given in Exhibit 2. It suggested that the capital program would easily hurdle Aromatic Chemicals’ required return of 10.35 percent for engineering projects.

Concerns of the Transport Division

Aromatic Chemicals owned the tank cars with which Liverpool received propylene gas from four petroleum refineries in England. The Transport Division, a cost centre, oversaw the movement of all raw, intermediate, and finished materials throughout the company and was responsible for managing the tank cars. Because of the project’s increased throughput, Transport would have to increase its allocation of tank cars to Liverpool. Currently, the Transport Division could make this allocation out of excess capacity, although doing so would accelerate from 2024 to now the need to purchase new rolling stock to support the anticipated growth of the firm in other areas. The purchase would cost £50 million. The rolling stock would have a depreciable life of 10 years, but with proper maintenance, the cars could operate much longer. The rolling stock could not be used outside Britain because of differences in track gauge. The Transport Division depreciated rolling stock using DDB depreciation for the first eight years and straight-line depreciation for the last two years.

A memorandum from the controller of the Transport Division suggested that the cost of the tank cars should be included in the initial outlay of Liverpool’s capital program. But Robert disagreed. He told Laura: The Transport Division isn’t paying one pence of actual cash because of what we’re doing at Liverpool. In fact, we’re doing the company a favour in using its excess capacity. Even if an allocation has to be made somewhere, it should go on the Transport Division’s books. The way we’ve always evaluated projects in this company has been with the philosophy of “every tub on its own bottom” — every division has to fend for itself. The Transport Division isn’t part of our own Intermediate Chemicals Group, so they should carry the allocation of rolling stock.

Accordingly, Robert had not reflected any charge for the use of excess rolling stock in his preliminary DCF analysis, given in Exhibit 2. The Transport Division and Intermediate Chemicals Group reported to separate executive vice presidents, who reported to the chairman and chief executive officer of the company. The executive VPs received an annual incentive bonus pegged to the performance of their divisions.

Concerns of the ICG Sales and Marketing Department

Robert’s analysis had led to questions from the director of Sales. In a recent meeting, the director had told Robert: “Your analysis assumes that we can sell the added output and thus obtain the full efficiencies from the project, but as you know, the market for polypropylene is extremely competitive. Right now, the industry is in a downturn and it looks like an oversupply is in the works. This means that we will probably have to shift capacity away from Rotterdam toward Liverpool in order to move the added volume. Is this really a gain for Aromatic Chemicals? Why spend money just so one plant can cannibalise another?” The vice president of Marketing was less sceptical. He said that with lower costs at Liverpool, Aromatic Chemicals might be able to take business from the plants of competitors such as Saone-Poulet or Vaysol. In the current severe recession, competitors would fight hard to keep customers, but sooner or later the market would revive, and it would be reasonable to assume that any lost business volume would return at that time.

Robert had listened to both the director and the vice president, and chose to reflect no charge for a loss of business at Rotterdam in his preliminary analysis of the Liverpool project. He told Laura:

Cannibalisation really isn’t a cash flow; there is no cheque written in this instance. Anyway, if the company starts burdening its cost-reduction projects with fictitious charges like this, we’ll never maintain our cost competitiveness. A cannibalisation charge is rubbish!

Concerns of the Assistant Plant Manager

Harry Green, the assistant plant manager and Laura’s direct subordinate, proposed an unusual modification to Robert’s analysis during a late-afternoon meeting with Robert and Laura. Over the past few months, Percy had been absorbed with the development of a proposal to modernize a separate and independent part of the Liverpool Works, the production line for ethylene-propylene-copolymer rubber (EPC). This product, a variety of synthetic rubber, had been pioneered by Aromatic Chemicals in the early 1990s and was sold in bulk to European tire manufacturers. Despite hopes that this oxidation- resistant rubber would dominate the market in synthetics, in fact, EPC remained a relatively small product in the European chemical industry.

Aromatic, the largest supplier of EPC, produced the entire volume at Liverpool. EPC had been only marginally profitable to Aromatic because of the entry by competitors and the development of competing synthetic-rubber compounds over the past five years. Percy had proposed a renovation of the EPC production line at a cost of £20 million. The renovation would give Aromatic the lowest EPC cost base in the world and would improve cash flows by £1,900,000 ad infinitum. Even so, at current prices and volumes, the net present value (NPV) of this project was -£3,000,000. Percy and the EPC product manager had argued strenuously to the company’s executive committee that the negative NPV ignored strategic advantages from the project and increases in volume and prices when the recession ended. Nevertheless, the executive committee had rejected the project, basing its rejection mainly on economic grounds.

In a hushed voice, Percy said to Laura and Robert: Why don’t you include the EPC project as part of the polypropylene line renovations? The positive NPV of the poly renovations can easily sustain the negative NPV of the EPC project. This is an extremely important project to the company, a point that senior management doesn’t seem to get. If we invest now, we’ll be ready to exploit the market when the recession ends. If we don’t invest now, you can expect that we will have to exit the business altogether in three years. Do you look forward to more layoffs? Do you want to manage a shrinking plant? Recall that our annual bonuses are pegged to the size of this operation. Also remember that, in the last 20 years, no one from corporate has monitored renovation projects once the investment decision was made.

Concerns of the Treasury Staff

After a meeting on a different matter, Robert Brown described his dilemmas to Oscar Dean , who worked as a senior analyst on Aromatic Chemicals’ Treasury staff. Oscar scanned Robert’s analysis, and pointed out:

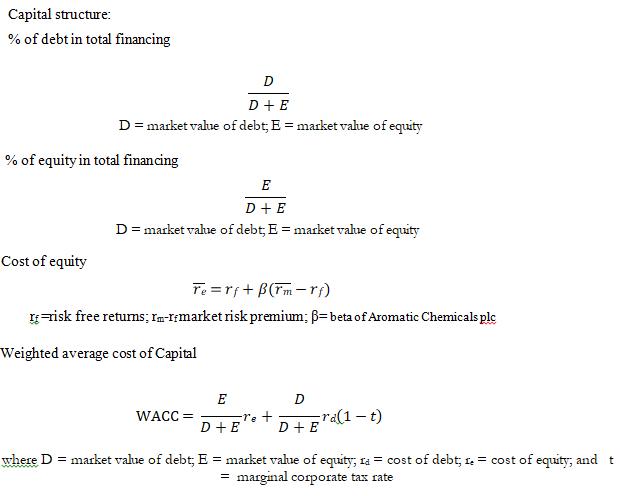

. . . cash flows and discount rate need to be consistent in their assumptions about inflation and the 12 percent hurdle rate you’re using for discounting free cash flows of this project is a nominal target rate of return (which in fact is Aromatic Chemicals’ cost of equity capital which is used for discounting equity cash flows, for discounting free cash flows, the weighted average cost of capital is more appropriate for project appraisal). The Treasury staff thinks this impounds a long-term inflation expectation of 3 percent per year. Thus, Aromatic Chemicals’ real (that is, zero inflation) target rate of return is 9 percent.

The Treasury staff also informed that the current U.K. 15-year Gilts yield is estimated as 3.88 percent and the historical market risk premium (which is the difference between the return on the FT all share index and yield on the UK 15-year Gilts) has been estimated at 5.80 percent. The current corporate tax rate is 25 percent. The current market value of the outstanding long-term debt (BBB rated bonds issued by the company in the past) is £275 million with yield on these bonds estimated at 7 percent. The Aromatic Chemicals has 1500 million shares outstanding. The current market price of its share is 250 pence. The beta for Aromatic Chemicals is 1.4.

The conversation was interrupted before Robert could gain a full understanding of Oscar’s comment. For the time being, Robert decided to continue to use discount rate of 12 percent because it was the figure promoted in the latest edition, Aromatic Chemicals’ capital-budgeting manual.

Evaluating Capital Expenditure Proposals at Aromatic Chemicals

In submitting a project for senior management’s approval, the project’s initiators had identified it as belonging to one of four possible categories: (1) new product or market, (2) product or market extension,

(3) engineering efficiency, or (4) safety or environment. The first three categories of proposals were subject to a system of four performance “hurdles,” of which at least three had to be met for the proposal to be considered. The Liverpool project would be in the engineering-efficiency category.

Impact on earnings per share: For engineering-efficiency projects, the contribution to net income from contemplated projects had to be positive. This criterion was calculated as the average annual earnings per share (EPS) contribution of the project over its entire economic life, using the number of outstanding shares at the most recent fiscal year-end (FYE) as the basis for the calculation.

Payback: This criterion was defined as the number of years necessary for free cash flow of the project to amortise the initial project outlay completely. For engineering- efficiency projects, the maximum payback period was six years.

Discounted cash flow: DCF was defined as the present value of future cash flows of the project (at the hurdle rate of 12 percent for engineering-efficiency proposals) less the initial investment outlay. This net present value of free cash flows had to be positive.

Internal rate of return: IRR was defined as being the discount rate at which the present value of future free cash flows just equalled the initial outlay-in other words, the rate at which the NPV was zero. The IRR of engineering-efficiency projects had to be greater than 12 percent.

Conclusion: Laura wanted to review Robert’s analysis in detail and settle the questions surrounding the tank cars and the potential loss of business volume at Rotterdam. As Robert’s analysis now stood, the Liverpool project met all four investment criteria:

- Average annual addition to EPS = 96 pence

- Payback period = 3,79 years

- Net present value = £222.74 million

- Internal rate of return = 6 percent

Laura was concerned that further tinkering might seriously weaken the attractiveness of the project.

Questions Requiring Answers

- How does Aromatic Chemicals evaluate its capital-expenditure proposals? Why such a complicated scheme is used for evaluation of proposals? Suggest simplification of this scheme providing your rationale.

- Evaluate the Transport Division’s suggestion? Does it have any merit?

- Evaluate the director of sales’ suggestion? Does it have any merit?

- Why did the assistant plant manager offer his suggested change? Does it have any merit?

- What did the analyst from the Treasury Staff mean by his comment about inflation? Do you agree with it?

- Explain the difference between the free cash flows and the equity cash flows mentioned by the senior analyst of Treasury.

- Calculate the cost of capital for The Liverpool Project using weighted average cost of capital of debt and equity and also confirming with your own calculations that the cost of equity capital for Aromatic Chemicals is indeed 12% as stated by the senior analyst of Treasury.

- How should Robert modify his DCF analysis?

- Evaluate the Liverpool project worth to Aromatic Chemicals with and without cannibalism?

- Examine the sensitivity of the project to changes in the manufacturing throughput, discount rate and gross margin with cannibalism.

- Assess the impact of the project on the earnings per share of the company and explain how EPS- EBIT analysis helps in deciding the financial policy of a company.

Exhibit 1: Comparative Information on the Seven Largest Polypropylene Plants in Europe

| Plant Location | Built in | Plant Annual Output (metric tons) |

Production Cost Plant per Ton (indexed to low-cost producer) | |

| CBTG A.G. | Saarbrun | 1999 | 3,500,000 | 1 |

| Aromatic Chem. | Liverpool | 1990 | 2,500,000 | 1.09 |

| Aromatic Chem. | Rotterdam | 1990 | 2,500,000 | 1.09 |

| Hosche A.G. | Hamburg | 1997 | 3,000,000 | 1.02 |

| Montecassino SpA | Genoa | 1981 | 1,200,000 | 1.11 |

| Saône-Poulet S.A. | Marseille | 1982 | 1,750,000 | 1.07 |

| Vaysol S.A. | Antwerp | 1992 | 2,200,000 | 1.06 |

| Next 10 largest plants | 4,500,000 | 1.19 |

Exhibit 2 : Aromatic Chemicals plc (A) Robert’s DCF Analysis of Liverpool Project

| Assumptions | |||

| Annual Output (metric tons) | 3,500,000 | Discount rate | 12.00% |

| Output Gain/Original Output | 6.0% | Depreciable Life (years) | 15 |

| Price/ton (pounds sterling) | 1300 | Overhead/Investment | 4.0% |

| Inflation Rate (prices and costs) | 0.0% | Salvage Value | 0 |

| Gross Margin (ex. Deprec.) | 12.00% | WIP Inventory/Cost of Goods | 4.0% |

| Old Gross Margin | 11.0% | Months Downtime, Construction | 1.6 |

| Tax Rate | 25.0% | After-tax Scrap Proceeds | 0 |

| Investment Outlay (mill.) | 300.00 | Preliminary Engineering Costs | 20 |

| Energy Savings/SalesYr. 1-5 | 1.20% | No of Shares (million) | 1,500 |

| Yr. 6-10 | 0.7% | ||

| Yr. 11-15 | 0.2% | ||

(Financial values in millions of British Pounds)

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| Year | Now | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | |

| 1. Estimate of Incremental Gross Profit New Output (tons) | 3,710,000 | 3,710,000 | 3,710,000 | 3,710,000 | 3,710,000 | 3,710,000 | ||

| Lost Output–Construction | -494,667 | |||||||

| New Sales (Millions) | 4179.93 | 4823.00 | 4823.00 | 4823.00 | 4823.00 | 4823.00 | ||

| New Gross Margin | 13.2% | 13.2% | 13.2% | 13.2% | 13.2% | 12.7% | ||

| New Gross Profit | 551.75 | 636.64 | 636.64 | 636.64 | 636.64 | 612.52 | ||

| Old Output | 3,500,000 | 3,500,000 | 3,500,000 | 3,500,000 | 3,500,000 | 3,500,000 | ||

| Old | ||||||||

| Sales | 4550.00 | 4550.00 | 4550.00 | 4550.00 | 4550.00 | 4550.00 | ||

| Old Gross Profit | 500.50 | 500.50 | 500.50 | 500.50 | 500.50 | 500.50 | ||

| Incremental Gross Profit | 51.25 | 136.14 | 136.14 | 136.14 | 136.14 | 112.02 | ||

| 2. Estimate of Incremental Depreciation | ||||||||

| New Depreciation | 40.00 | 34.67 | 30.04 | 26.04 | 22.57 | 19.56 | ||

| 3. Overhead | 12.00 | 12.00 | 12.00 | 12.00 | 12.00 | 12.00 | ||

| 4. Prelim. Engineering Costs 20.00 5. Pre-tax Incremental | ||||||||

| Profit | (20.75) | 89.47 | 94.09 | 98.10 | 101.57 | 80.46 | ||

| 6. Tax | ||||||||

| Expense | (5.19) | 22.37 | 23.52 | 24.52 | 25.39 | 20.12 | ||

| 7. After-tax Profit | (15.56) | 67.10 | 70.57 | 73.57 | 76.18 | 60.35 | ||

| 8. Cash Flow | ||||||||

| Adjustments | ||||||||

| Less Capital Expenditures | (300.00) | |||||||

| Add back Depreciation | 40.00 | 34.67 | 30.04 | 26.04 | 22.57 | 19.56 | ||

| Less Added WIP inventory | 16.85 | -22.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| After-tax Scrap | ||||||||

| Proceeds 0.00 | ||||||||

| 8. Free Cash Flow | (300.00) | 41.29 | 79.44 | 100.61 | 99.61 | 98.74 | 79.91 | |

| 9 | EPS | 2.75 | 5.30 | 6.71 | 6.64 | 6.58 | 5.33 | |

| NPV = | 222.74 | |||||||

| IRR = | 24.6% | |||||||

| Average EPS | 4.96 | pence | ||||||

| Payback period | 3.79 | years | ||||||

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 2028 | 2029 | 2030 | 2031 | 2032 | 2033 | 2034 | 2035 | 2036 |

| 3,710,000 | 3,710,000 | 3,710,000 | 3,710,000 | 3,710,000 | 3,710,000 | 3,710,000 | 3,710,000 | 3,710,000 |

| 4823.00 | 4823.00 | 4823.00 | 4823.00 | 4823.00 | 4823.00 | 4823.00 | 4823.00 | 4823.00 |

| 12.7% | 12.7% | 12.7% | 12.7% | 12.2% | 12.2% | 12.2% | 12.2% | 12.2% |

| 612.52 | 612.52 | 612.52 | 612.52 | 588.41 | 588.41 | 588.41 | 588.41 | 588.41 |

| 3,500,000 | 3,500,000 | 3,500,000 | 3,500,000 | 3,500,000 | 3,500,000 | 3,500,000 | 3,500,000 | 3,500,000 |

| 4550.00 | 4550.00 | 4550.00 | 4550.00 | 4550.00 | 4550.00 | 4550.00 | 4550.00 | 4550.00 |

| 500.50 | 500.50 | 500.50 | 500.50 | 500.50 | 500.50 | 500.50 | 500.50 | 500.50 |

| 112.02 | 112.02 | 112.02 | 112.02 | 87.91 | 87.91 | 87.91 | 87.91 | 87.91 |

| 16.95 | 14.69 | 12.73 | 11.03 | 14.34 | 14.34 | 14.34 | 14.34 | 14.34 |

| 12.00 | 12.00 | 12.00 | 12.00 | 12.00 | 12.00 | 12.00 | 12.00 | 12.00 |

| 83.07 | 85.33 | 87.29 | 88.99 | 61.56 | 61.56 | 61.56 | 61.56 | 61.56 |

| 20.77 | 21.33 | 21.82 | 22.25 | 15.39 | 15.39 | 15.39 | 15.39 | 15.39 |

| 62.30 | 64.00 | 65.47 | 66.74 | 46.17 | 46.17 | 46.17 | 46.17 | 46.17 |

| 16.95 | 14.69 | 12.73 | 11.03 | 14.34 | 14.34 | 14.34 | 14.34 | 14.34 |

| 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 79.25 | 78.69 | 78.20 | 77.77 | 60.52 | 60.52 | 60.52 | 60.52 | 60.52 |

| 5.28 | 5.25 | 5.21 | 5.18 | 4.03 | 4.03 | 4.03 | 4.03 | 4.03 |

Marking Guidelines

Each task is being marked according to the following marking rubric:

- How does Aromatic Chemicals evaluate its capital-expenditure proposals? Why such a complicated scheme is used for evaluation of proposals? Suggest simplification of this scheme providing your rationale.

(2 marks each for EPS and Payback and 4 marks for NPV and IRR and 2 marks for suggestion) (Total 10 marks)

- Evaluate the Transport Division’s suggestion? Does it have any merit?

- Evaluate the director of sales’ suggestion? Does it have any merit? (6 marks)

- Why did the assistant plant manager offer his suggested change? Does it have any merit? (5 marks)

- What did the analyst from the Treasury Staff mean by his comment about inflation? Do you agree with it? (6 marks)

- Explain the difference between the free cash flows and the equity cash flows mentioned by the senior analyst of Treasury. (5 marks)

- Calculate the cost of capital for The Liverpool Project using weighted average cost of capital of debt and equity and also confirming with your own calculations that the cost of equity capital for Aromatic Chemicals is indeed 12% as stated by the senior analyst of Treasury.

Market value of equity( shares) = market capitalisation

Market value of shares= market capitalisation =number of shares*share price

- How should Robert modify his DCF analysis?

Engineering study:

Corporate overhead allocation: Cannibalisation of the Rotterdam plant:

Use of excess capacity in tank cars:

Whose interests are at stake.

The interdependence of excess capacity and the cannibalization issue.

Changes in inventory:

Adjustment for inflation:

- Evaluate the Liverpool project worth to Aromatic Chemicals with and without cannibalism?

Without cannablism (using NPV and IRR) With cannablism (using NPV and IRR)

- Examine the sensitivity of the project to changes in the manufacturing throughput, discount rate and gross margin with cannibalism.

The sensitivity analysis and its purpose

Comments on relative sensitivity of NPV and IRR to the manufacturing throughput and gross margin than discount rate.

Limitation of the sensitivity analysis as a tool for assessing the risk of the project.

- Assess the impact of the project on the earnings per share of the company and explain how EPS- EBIT analysis helps in deciding the financial policy of a company.

Calculation of Average EPS : Without and with cannibalism Impact of EPS on share price:

Explain how EPS-EBIT can be used as on one of the tools for deciding the financial policy of a company.

For REF… Use: #getanswers2002491