- Case StudyHelp.com

- Sample Questions

Case Study: Wind Power Generate or

WindGen, a Brazilian company, manufactures and supplies wind turbines for offshore wind power installations. WindGen wishes to sell a set of 20 wind turbines to E-Power (Scotland), a recently privatized company, and E-Power wishes to purchase a set of 20 wind turbines from WindGen. E-Power is keen for this transaction to go ahead.

E-Power is prepared to pay up to £1.2 million for these wind turbines provided it achieves satisfaction on certain points. Otherwise, the value of these wind turbines falls to as little as £500 000.

It is very important that E-Power gets full warranty protection and it would like liquidated damages if WindGen does not install the wind turbine within three months of ordering. WindGen could insure this as one of their business risks, but they want to charge the premiums for this to E-Power. E-Power would like WindGen to accept a repairing obligation for the next three years.

It is essential to E-Power that the wind turbines are up and running in its offshore Scotia Field within the next Three months and it would like there to be significant (20%) liquidated damages if this does not occur, but it would settle for as low as 10%.

WindGen would like the currency of the contract to be Euro, while E-Power wants it denominated in the US dollars, but E-Power can be fairly relaxed on this point.

Price is a thorny one for WindGen. Any payment below £750 000 and it would make no profits. This is the fundamental point as far as WindGen is concerned, especially as E-Power wants the wind turbine delivered to its newly proven development bloc, situated in the North Sea, and insists that it is installed in an extremely narrow weather window.

WindGen has offered to guarantee the working condition of the wind turbine for the next year on a full repair or replacement basis, but it is very reluctant to go beyond that because of the expense and the technical risks that are always associated with new fields.

WindGen has indicated that it is willing to have the wind turbine operational within the next three months. It has also indicated its willingness to consider liquidated damages if the wind turbines are not installed within the three months following E-Power’s order, and it has suggested a figure of 3%.

It says it wants a strong force majeure (‘excusable delay’) clause to protect it against unforeseen delays beyond its control, such as the weather and unforeseen technical difficulties arising in the North Sea.

Required:

1. What are E-Power’s interests in this case?

(8 marks)

2. What are WindGen’s interests?

(8 marks)

3. What are the negotiable issues in the case and their related priorities for each party?

(8 marks)

4. How might E-Power set its entry & exit points in this negotiation?

(8 marks)

5. What justification would you give for a proposal that E-Power might offer to WindGen?

(8 marks)

Essay Questions

Essay 1

Jose was preparing for negotiation with a new client but wasn’t sure how to open the discussions. He didn’t want to be too soft and give the new client a chance to push him early on for discounts, but at the same time, he was worried about going in too hard and putting the new client off before their relationship had a chance to begin. Jose felt that both options were risky, but he needed to decide quickly before his meeting. Getting it wrong at this early stage could cause problems in the long term with the client.

Why and how does the Prisoner’s Dilemma game assist our analysis of the problem of trust in negotiation, and how could it help Jose with his decision?

(20 marks)

Essay 2

“You seem very worried Terry,” said Sophie. “Yes, so would you be in my shoes. The last time I had a negotiation with Tristan, he pushed for unrealistic deadlines, opened with outrageous terms and even walked out of the meeting when I didn’t give him enough concessions. I had to give away so much just to keep him as a client; it hardly seems worth it. It undermined my confidence, and I have to face him again tomorrow, what should I do?” He replied.

Why do some negotiators practise manipulative ploys?

(20 marks)

Essa y 3

“Do we have to negotiate? There must be another way to get this proposal agreed within the company?” Jan suggested.

Why might you use an alternative to negotiation when making decisions and what are the possible advantages and disadvantages of doing so?

(20 marks)

Examiners solution 2010 Case Solution

1. What are E-Power’s interests in this case?

(8 marks)

Interests are the motivations for preferring specific solutions to problems. They are the ‘fears, hopes and concerns’ of E-Power. They are reasons ‘why’ E-Power wants certain things to happen.

E-Power is a profit-making privatized company and its prime interests are to maintain or raise shareholder value in a sustainable manner. In the case, its main interest is to acquire a wind turbine and have it operating quickly because, presumably, it needs a working wind turbine on its offshore field (the need is not specified).

E-Power’s interests are constrained by the need to limit its expenditures even if all its requirements are met, and limit them even more if they are not. The wind turbines deliver its interests but not at any price. Presumably, E-Power will search the market if WindGen cannot meet its needs.

For undisclosed reasons, E-Power must cover its risks if the wind turbines are not operating quickly and if it needs repairs within three years. This suggests that they are covering their risks, which makes them an interest.

- What are WindGen’s interests?

(8 marks)

Definition of interests as in Question 1.

As a commercial venture, WindGen’s main interest is to make sustainable profits and maintain or increase shareholder value.

WindGen only meets its interests if it meets E-Power’s agreed requirements on the delivery date and some part of its requirement for a warranty. It wishes to reduce its obligations on liquidated damages as this might jeopardize its profits.

Price is related to its main interests in profitable business and price is related to delivery within the time stated and the weather window.

- What are the negotiable issues in the case and their related priorities for each party? (8 marks)

A negotiable issue is the agenda item. It is quantifiable, and it delivers the party’s interests. It is what the negotiator ‘wants.’

Negotiable issues are prioritized because negotiators have varying degrees of preference for what they want and it is these differences in the value of each issue which gives the negotiators trading possibilities when it comes to proposing and bargaining.

Issues can be prioritized as High (must get or no deal), Medium (would like to get within ranges or it puts pressure on the viability of the deal) and Low (would like to get, but will not affect the deal).

In this case the issues and priorities for the parties can be shown as follows:

| Issues | WindGen priority | E-Power priority |

| Price of the Wind turbine | High | Med |

| Installation date | Low | High |

| Currency | Low | Low |

| Warranty | Low | High |

| Liquidated damages | Med | Low |

| Force majeure definition | High | Med |

4. How might E-Power set its entry & exit points in this negotiation?

(8 marks)

Entry and Exit points are part of the preparation process. They are the ranges within which a negotiator is prepared to deal. The entry point is where they are willing to start the negotiation, and the exit point is the point beyond which they are unwilling (or even unable) to deal. Entry points should be defensible and credible.

From E-powers point of view, they might set the entry and exit points for the issues as follows:

| Issues | Entry | Exit |

| Price of the Wind turbine | £500 000 | £1.2m |

| Installation date | 2 months | 3 months |

| Currency | US$ | Euro |

| Warranty | 5 years | 3 years |

| Liquidated damages | 20% | 10% |

| Force majeure definition | Strong | Medium |

- What justification would you give for a proposal that E-Power might offer to WindGen?(8 marks)

A proposal is a tentative suggestion, specific or vague in the condition, but always vague in the offer and should be presented in the ‘IF–THEN’ format. For example, ‘if you give me some of what I want, then I could give you some of what you want.’

‘If you agree to deliver the wind turbine on site and operating satisfactorily within three months and accept liquidated damages at 20 per cent, then we could pay more than $900 000 dollars for it’ might be where E-Power would start.

It would justify the proposal as meeting its minimum terms – delivery on time and operate is a prime interest of E-Power. Everything must click because downtime and late delivery cannot be tolerated given the expense of shutting the field for maintenance and repairs.

The liquidated damages are set high to discourage any ambiguity about E-Power’s requirements, as are the premium costs for insurance against WindGen’s failures. Narrow force majeure provisions (‘acts of God’ only) are required to protect E-Power’s interests as are the requirement to pay in US dollars.

Essay 1

Why and how does the Prisoner’s Dilemma game assist our analysis of the problem of trust in negotiation, and how could it help Jose with his decision?

(20 marks)

The original Prisoner’s Dilemma (PD) type games explored the tension between coping with the risks of coordination and suffering from the lower or negative pay-offs from defection. The games can be played without content (the red and blue game) or with content using a short scenario (the original PD game, or the Currency game, or the War and Peace game, etc.). Many authors have analyzed the games and their derivatives (Game Theory) in a variety of disciplines, as well as in negotiation studies. While the question specifies the PD game, it would be acceptable to discuss the other games as long as they have a structure based on the PD type of games (broadly, doing what is best for oneself as opposed to doing what is best for both parties).

First, a brief description of PD games is required, with some understanding shown of the structure of the game rather than merely describing it. In essence, PD is about the risks of trust and about the behaviors prompted by defensive intentions to protect from exploitation (or red play) by the other party, or of having aggressive intentions to exploit the other party in the hope that it will play blue. PD shows that because of these risks, players acting independently are often led to choices (or plays) which produce sub-optimal outcomes (lose-lose; lose–win; win-lose) compared to what they could have achieved if they had been able to co-ordinate their play (win-win).

By illustration, we can describe the original scenario for PD (the numbers representing the pay-offs vary between accounts and are less important than understanding the nature of the dilemma).

A brief account of the PD game. Two persons have been arrested on suspicion of having committed a serious crime and have been placed in separate cells with no possibility for communication between them. The District Attorney (the game was created in the United States in 1950) has insufficient evidence to secure a conviction in a court but has sufficient evidence to be sure that the prisoners carried out the crime. He devises an offer to be put to each prisoner separately which will assist him getting at least one, if not both, of them, convicted. Each prisoner is told that a deal is possible when they choose between confessing to the crime and not confessing. If they confess and their partner does not, then their evidence will be used to convict the son- confessor, who will receive 20 years and they will be released. If they confess and their partner confesses, they will both receive ten years (it was a serious crime). If they do not confess, but their partner does, the outcome will be reversed with them getting 20 years and their partner being released. If neither of them Confesses, they will both be convicted on a lesser charge and receive three years. The dilemma is: what should a prisoner do?

On the face of it, the choice of confessing and not confessing is easy; both of them should not confess because this has the minimum risk of only three years, and, if they could safely co-ordinate their choices to deliver a win-win outcome, this choice would be best for both of them. But the scenario precludes safe co-ordination – Each prisoner is in a separate cell and has to make his choice without knowing what the other has chosen. If for them both not confessing is the optimum choice (though not of course for society and the upholding of law and order) they run the risk that their partner might not choose this option.

What of their choices without a safe and sure means of co-ordination?

If prisoner A decides not to confess, he must be sure that his partner, prisoner B, does not confess as well. Otherwise, he risks 20 years in prison if prisoner B confesses. If he believes prisoner B will confess, his best choice (self-protection) is to confess as well, because ten years in prison (lose-lose) is better than 20 years. Also, if he confesses and finds that his partner has not confessed, he will go free (he wins, his partner loses), and going free beats ten years.

However, as neither prisoner can be sure what his partner will do, they cannot formulate an optimum or safe win-win strategy. Hence they are in a dilemma: ‘if my partner thinks I will not confess, he may not confess too, which is to our mutual (win-win) benefit, or will he confess (i.e., defect) to my certain disadvantage? If, however, he is likely to defect by confessing, should I stick to my choice of not confessing or should I change my mind and confess? ‘What is my partner thinking about, what I think he is thinking about, what I am thinking he is thinking …?

Even if the players can co-ordinate their play before they are separated and can reach an agreement not to confess in pursuit of the win-win outcome of only three years each, how can either be sure that the other will stick to the deal? If your partner defects and confesses, twenty years in jail is an expensive way to learn about the vagaries of one’s partner’s promises. This leads the players to choose a sub-optimal lose-lose play (in this game, defection by confessing) resulting in each serving ten years. They will also have the dubious benefit of having ten years to explain to each other why they defected and confessed – was it a failed attempt to trap the other into doing twenty years so that the defector could go free?

The players are driven to a sub-optimal play not because they want to but because they have to. Defection is forced upon them because they think the other will defect (protection of self to avoid twenty years in prison). Trust to achieve a win– the win is overwhelmed by the risks of trust (them losing and their partner winning).

In negotiation, there are similar dilemmas and similar problems of trust. We negotiate because we do not know the outcome that is satisfactory to both parties; we know what may be satisfactory to us and we also know that whatever that satisfactory outcome is, we would be even happier with a deal that is even more satisfactory to us. Caution is advisable, but suspicion breeds self-protection and a failure to co-ordinate or to deliver the fruits of co-ordination.

The concept of win-win outcomes is in widespread use in negotiation literature. The win-win or Nash outcome (48 each in red versus blue games which maximise the product of their net gains) is available but rarely occurs because players are driven either by self-protection (‘I’ll play red because I believe my partner will play red’) or by exploitation (‘I’ll play red because I am sure my partner will play blue’).

An elaboration of the implications of the Nash solution only being chosen by 8 per cent of playing pairs in red–blue games (from observation) gains extra marks.

The act of playing red is self-fulfilling. If both play red they confirm the self-protection motive; if one plays blue and loses to red play, they switch to red play in the next round to protect themselves (brief reference to Tit-for-Tat strategies gain marks). The player who played red to exploit now faces the prospect that his partner is alerted to his exploitative intentions which will force the blue player to switch to red in retaliation. Should the red player stick with red play to protect himself or switch to red as an ‘apology’? The road to a lose-lose outcome is wide and slippery.

In one-off exchanges (like the original PD) red play predominates because trust is perceived to be too risky –They both end up doing ten years. In red–blue, just under half of the players play blue in the first round, but Red is still the choice of just over half of the players. Many partners manage to agree on the mutual blue play before the game is over, but the rest get stuck into a red–red cycle and end up with lower positive scores than they needed to (i.e., well short of a Nash solution).

Over many negotiations, players can learn to find ways of co-operating to produce win-win outcomes. The evolution of blue–blue play from Tit-for-Tat strategies ensures that negotiated outcomes produce better results than the alternatives of defection or cheating (e.g. ‘nibbling’). Win-win negotiation successes dominate exploitative and coercive distribution of whatever is at stake because people who feel cheated avoid cheaters, which is why, over the long run, negotiation is more closely associated with wealth creation and harmonious relations than coercion and violence. Negotiators learn to play blue–blue with those with whom they have strong relationships and to avoid people who defect to exploit them. This does not obviate the need to be wary of unproven negotiating partners. There is a risk in trust.

Jose needs to be careful of his approach to the new client. By looking at the simplified PD – the red/Blue game, his best approach is to use Tit-For-Tat. Devised by Axelrod, the TFT method states:

- Always start out by co-operating.

- Reward/punishment responses from then on based on what the other person plays in the previous round.

For his meeting with the new client, Jose should start the negotiation in an open and co-operative manner. If this is reciprocated, this behavior can continue and over time trust will be developed.

If it is not reciprocated, Jose can switch to protect himself from risk and become less accommodating. Only when the client shows a move back to co-operating should Jose do the same. He should not hold any grudges but move forward towards co-operation again.

Essay 2

Why do some negotiators practise manipulative ploys?

(20 marks)

This is not a repetition of Question 1 and references to PD or red, and blue dilemma games will NOT attract marks. It is about the tactical choices made by negotiators in ‘live’ negotiations. Examples from real negotiations will attract discretionary marks.

Identification of red manipulative behavior (briefly contrasted with blue behavior but not an in-depth Exposition) is essential: aggression, open coercion, threatening, bullying, ‘taking,’ etc. Identification of ‘devious’ red behavior – the act of gaining red outcomes from hiding your red intentions.

Defining the purpose of manipulation: to influence the perceptions of the outcome and lower these expectations so that the red manipulator gains more than the other player (“more for me means less for you”). As these ‘gains’ (even if only short-term) can be significant, the red manipulator has an economic incentive to behave in this manner.

Most candidates describe the three most famous ploys, reproduced in the text, namely The ‘Bogey,’ the ‘Krunch’ and the ‘Nibble.’ Many candidates list others (e.g. ‘Russian Front,’ ‘Good guy/Bad guy,’ ‘Mother Hubbard’, ‘Salami,’ etc.).

The Essay should be about ‘why’ negotiators manipulate and not just a description of famous ploys.

All red behavior is manipulative. Red behavior aims to get something for nothing (e.g., ‘more for me means less for you’). It can come in several forms from outright bullying, intimidation, domineering and aggression. It can also be more subtle, even good mannered and, on occasion, covert. In contrast, purple behavior aims to trade something for something (e.g., ‘more for me means more for you’) but in its submissive blue form ends up giving something for nothing, which is the reverse stance of the negotiator relying on red behavior.

Tactical ploys can work with the submissive blue negotiator. In fact, without submissive blue negotiators, there would be no role for tactical ploys. Only if the tactical negotiator gets something for nothing from somebody prepared to give something for nothing is it worth being a manipulator. Against assertive blue negotiators, tactical ploys are useless because assertive negotiators insist on the exchange principle: ‘if you give me some of what I want then I will give your some of what you want.’ They see one-way red deals for what they are – attempts to exploit them.

Experience is a great teacher and people subjected to tactical ploys soon learn that they were disadvantaged in the exchange and they seek to protect themselves from similar exploitation on later occasions. There are two motives for playing red: to exploit the other player (take advantage of their blue gullibility) or to protect oneself from the other player (‘do unto others before they do it unto you’). These two motives explain why negotiators resort to tactical ploys.

The exploiter motive corresponds to the image of the ‘street-wise’ dealer and attracts a large audience of would-be ‘tough guys,’ ready to mix it with other tough guys. They seek to win at the other negotiator’s expense. They get a buzz from defeating the other negotiator, from winning the largest slice of whatever is going, from getting something for nothing (or very little in exchange). They thrive in short-term businesses (used car sales, estate and house agents and brokers, and the one-off contracts). Above a certain level, they can increase the costs of a business sector way beyond their gains, e.g., the construction industry with its myriad of claims and counterclaims for variations and defects. Chester Karass made a successful career teaching people how to survive in the negotiation (i.e., tactical ploys) jungle.

The protector motive is a more acceptable cause of resorting to tactical ploys. This is summed up in the text as: ‘I defect, i.e., use ploys, not because I want to but because I must.’ Like the footballer who justifies his fouling of other players because it is necessary to ‘get his retaliation in first.’ It is fear of what the other negotiator might intend to do to you that drives you to ploys. I expect him to try to cheat me by padding his prices, and hence, it is legitimate to hit him with the Krunch (‘you have to do better than that’). Of course, exposure to the Krunch teaches negotiators to pad their prices because they expect to be Krunched, which perpetuates the ploy cycle.

Expecting the Nibble to be employed by your customer; you Nibble back, slicing something off here and something off there. You pad your prices to allow for late payments and demands for freebies. She ‘Bogeys’ you – ‘I love your product, but my budget won’t allow me to place an order,’ so your padded prices serve to protect your true price. You come down in price in response to her bogey, so the next time round she hits you with the Krunch! To make money, you Nibble. And so it goes on until you are so accomplished at ploys that you forget that your original motivation was to protect yourself. Meanwhile, your behavior is indistinguishable from the exploiter. Indeed, you can justify exploitation because this enables you to get back what you lost to other exploiters!

Evaluation of the weaknesses of tactical ploys – and the benefits of assertive purple trading in support of the above analysis can be worth marks, but as a substitute for answering the questions on why ploys are resorted to, they are less convincing.

Evidence of understanding how some other identified red ploys (‘tough guy/soft guy,’ ‘over-valuing a feature of the deal,’ ‘setting pre-conditions,’ ‘high initial demands,’ ‘threats’ and ‘pre-emptory deadlines,’ etc.,) are intended to work will attract marks. A brief reference to some of the ‘blue’ ploys can supplement but not substitute for an answer.

Evidence of understanding the structure of ‘Dominance,’ ‘Shaping’ and ‘Closing’ manipulations may attract discretionary remarks, but only in an evaluative context and not as a pure description of the phases.

Essay 3

Why might you use an alternative to negotiation when making decisions and what are the possible advantages and disadvantages of doing so?

(20 marks)

Negotiation is one among several ways of making decisions. It is not appropriate in all circumstances, nor is it a better means of deciding for others.

Negotiation is a widely used option where conditions for it exist. These conditions normally include the mutual dependence of each decision-maker on the other. If someone needs your consent for you to do something he/she wants you to do and to which you cannot unilaterally say ‘no,’ nor can he/she make you do it, it may be possible to negotiate something that meets both your own and that person’s concerns. This usually involves you getting something, tangible or intangible, in return for your consent. But if you have nothing to trade – he/she does not need anything you have, including your consent, nor does he/she have anything in his/her gift that would persuade you to consent – then negotiation is unlikely to be appropriate.

Negotiation is the process by which we obtain what we want from someone who wants something from us. It is a two-way transaction. It is about exchanging something for something. Because negotiation takes time and, perhaps, considerable effort, it should be used only when the likely outcome justifies the ‘costs’ regarding time and effort. Spending thirty minutes in a retail shop negotiating to get a cent off from the price of a packet of rice, suggests you value your time to be worth 2 cents an hour.

Negotiation is not about a foregone conclusion; the outcomes may vary considerably. They are not predictable. When you need someone’s consent, negotiation may be appropriate (you could try persuasion first).

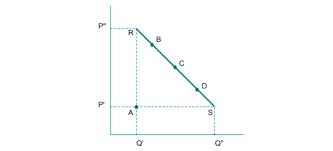

The benefits of negotiation include the likely willingness of the negotiators who have contributed to the joint decision on the implementation of what they have agreed. Could be illustrated by the Benefits of Bargaining diagram:

Figure 8.1 ‘The benefits of bargaining’ from the text

A short description of Figure 8.1 is required.

Other decision making methods include:

- Persuasion, Saying No, Chance, Problem Solving, Arbitration, Mediation, Coercion, Instruction and Giving In.

One party to a decision can simply reject it. ‘No’ is an appropriate decision in some circumstances (when you cannot accept the proposal, but you can endure the consequences of rejecting it) and not in others (when you cannot endure the consequences of rejection – such as in a Russian Front ploy).

You could try persuasion, which is what most selling skills are about. Probably the first thing everybody tries. Sometimes it works; as often it does not. Some methods of persuasion are more successful than others (showing how somebody will benefit from the decision is better than rubbing their noses in how much it will hurt them if they reject it). There are also the various techniques of influencing skills. Persuasion may be least costly when it works, but time-consuming when it does not. Rejection of a persuasive effort may provoke bad feelings, especially when a party feels its efforts have been rejected out of malice or some other negative motivation.

Problem-solving is often given greater credence than it merits in practice. The ideal of problem-solving is excellent and it can be made to work providing the parties to the decision agree that they share the problem – so that it becomes a joint problem with a joint solution – and that the parties trust each other in all respects. If either condition is absent, it may end in tears and reversion to some other method. Principled Negotiation is one such problem-solving method (brief elaboration is worth extra marks).

You could toss a coin or its equivalent – and many do. This leaves the outcome to chance and not to the influence of the parties. If you are indifferent to the proposed outcomes or you have no other option, then a 50 percent chance of an outcome you want to happen may not unduly worry you. But where the stakes are high, you have a lot of risk by allowing a chance to determine what you get.

It is possible to resort to arbitration, providing you can agree on the arbiter(s) and the method to use, such as pendulum, panel or individual arbitration (brief exposition of these systems is worth extra marks). Arbitration takes the decision out of the hands of the parties and hands it to ‘neutral’ third party. Neutrality is not always possible, and arbitration may be abused. A party can deliberately deadlock a negotiation to get the final decision passed to arbitration. If the Arbiter improves on the other party’s last offer, then the party that deliberately deadlocked to invoke arbitration has done better than it would have got by accepting the ‘final’ offer. They also can respond by rejecting the arbiter’s decision, but this may not help them if the arbiter sticks with the decision.

The coercive method applied to decision-making is a risky strategy – it can result in compliance with the enforcer’s demands, or result in retaliation with counter-coercion (perhaps violence). There are times when coercion is probably effective, such as when the party has the means and the will to enforce compliance, but coercion is damaging to relationships and may result in a steadily worsening situation.

Instruction is a legitimate method of decision making, provided the person instructed accepts the instruction and has the means to carry it out. You do not need to negotiate or even discuss every instruction that you give to the people who are paid to carry them out. The main point of a supervisor – supervised relationship is the economy of a decision-making process by which those who are normally contracted to accept instruction will, in fact, implement instructions without further ado.

The other side of instruction and coercion is that of giving in, which is something we all do from time to time. Life would be difficult if we did not do so. Insisting on negotiating everything would be time-consuming and stressful and in the main pointless. However, giving in on issues during a negotiation would also be self- defeating because once a negotiator gives in on one issue the other negotiator will expect – and push for – that person to give in on other issues.

It is also possible that a decision could be made to postpone a decision on the substantive issue(s). This sometimes buries the issue in delay and prevarication. Sometimes an inquiry, for example, can bury the issue in boredom – by the time the decision is announced (if it ever is), most people have forgotten its relevance.

The important thing to remember is that no single decision-making method is superior in all circumstance to another. It all depends on the circumstances.