- Case StudyHelp.com

- Sample Questions

Launching Mobile Financial Services in Myanmar: The Case of Ooredoo

Looking for Launching Mobile Financial Services in Myanmar: The Case of Ooredoo? Get Answers Case Study on The Case of Ooredoo. Casestudyhelp.com has a team of more than Masters & PhD expert writers that make future of million students in Australia, UK and USA. Be it your online assignment help, Custom Essay Writing or Dissertation Writing Services, Casestudyhelp.com is the one-stop solution for all.

October 2014: Dawn of Myanmar’s Modern Age

It had been two weeks since Ooredoo had launched its telecom network in Myanmar. Unlike their neighbors in Cambodia, Laos, and Thailand, where estimated average cell phone penetration was 77%, less than 10% of Myanmar‒s population had mobile phone accessi prior to Ooredoo‒s rollout.1 Yet those statistics were rapidly changing. The price of SIM cardsii, as measured by sales of government-owned Myanmar Posts and Telecommunications (MPT) SIM cards, had just plummeted from a reported range of $80む$100iii on Myanmar‒s grey market to the governmentむmandated face value of $1.50. (MPT was the only mobile operator in Myanmar prior to Ooredoo‒s launch╆� On week one of the launch, over one million Ooredoo- branded cards were sold╇ leaving Ooredoo‒s newly minted telecom infrastructure struggling to keep up with demand.

In June 2013 Ooredoo had been awarded one of two telecommunication licenses to operate in mobile-starved Myanmar; the licenses were finalized in February 2014. Winning the license had started the clock ticking for the Ooredoo Myanmar team and its key competitor, Telenor,iv which planned to launch its services in November 2014.2 Telenor and Ooredoo had both committed to providing voice service to at least 75% of the country and data service to over 50% of the country within five years.

With voice and data service as Ooredoo‒s first priority, mobile financial services (also known as mobile money) were expected to follow quickly. Mobile money め using a cell phone as a bank accountめwas prevalent in emerging markets where a high percentage of the population was unbanked, especially where people were more likely to own a mobile phone than to have a bank account. In emerging markets, the most common uses of mobile money platforms were for money transfers (typically to send funds from people in urban locations to family members in rural areas) and bill payment. According to the Center for Financial inclusion, 90% of Myanmar‒s population did not have access to formal financial services.

VIDEO EXCERPTS

Link 1: King on the Myanmar opportunity and challenges

Link 2: Gorman on the Myanmar opportunity and challenges

The Business Problem

Ooredoo Myanmar CEO Ross Cormack looked to Digital Services Senior Director Julian Gorman, supported by Mobile Financial Services Head Consultant Thomas King, to formulate a game plan for mobile money in Myanmar once the company‒s first wave of services had launched. As King explained, Myanmar was a slightly different animal from most other emerging markets╈ ⦆We‒re involved in a totally new network╇ we‒re building our towers from scratch╇ building our customer base from scratch╊Usually when you launch mobile money it‒s on an established network╆を5

Gorman had to make some critical decisions by the end of 2014. Should Ooredoo launch mobile financial services in Myanmar in early 2015? And if so, what services should be provided and in what form: as a mobile wallet (an e-account that customers handled directly to transfer money from their account to other customers with a mobile wallet), or an over-the- counter (OTC) service (where payment and money transfers were processed by handing cash to an agent who transferred the money on the customer‒s behalf)? What resources would be required to launch the services? Was the Myanmar customer ready for mobile money? How would the launch of mobile financial services affect Ooredoo‒s core airtime business′ As Gorman considered these questions, he reviewed the situation in Myanmar, the telecommunications industry, mobile financial services, the potential market size, and Ooredoo‒s competitive environment.

The Country: Myanmar

Located in Southeast Asia, in 2013 Myanmar had a population of approximately 53 million.6 The country shared borders with Laos, Thailand, Bangladesh, India, and China. Its estimated GDP in 2013 was USD 59.4 billionめ15% that of Thailand.7 It was also estimated that Myanmar had the lowest per capita income in the Southeast Asia region, with approximately 32% living at or below the poverty line. The World Bank reported that Myanmar‒s literacy rates were about 92%. 8 According to a recent consumer survey, men were the traditional income providers for households (71%); however, decisions on family finances and grocery shopping were primarily handled by women (78%). The infrastructure of the country was poor, with 75% of the population living without electricity, 50% of the roads inaccessible during monsoon seasons, and extremely limited connectivity beyond the top 20 cities in the country. (See Exhibit 1 for additional demographic information as reported by TNS, a local private research firm.)

A former British colony, Myanmar (called Burma until 1989) was first administered as a province of India before becoming a self-governing colony and ultimately an independent state in 1948. Until 2010 the country had been largely controlled by the army. In April 2012, following the release of hundreds of political prisoners, preliminary peace agreements with major armed ethnic groups, and the enactment of laws that provided better protections for basic human rights, there was an easing of international restrictions, and key sanctions were lifted by the European Union, the United States, and other nations. The mood of the country had shifted; as long-time Myanmar resident Jason Copland (market research director at TNS Global) noted, ⦆The biggest change was the freedom of expression that people had. And it certainly made for a lighter mood in the street and in the office╊People were feeling more optimistic╆を

The financial sector in Myanmar was particularly underdeveloped. According to the Economist, as of September 2013 Myanmar‒s イエ banksめfour of which were wholly state owned and another 11 of which were at least partially government owned or managed め had a total of 863 branches. By comparison, Thailand, with just 14,000 more people, had nearly 7,000 more branches.

There was also a generalized lack of trust in banks, following several runs on them in recent history. Many employers paid their workers in cash, as King explained:

So right now if you‒ve got a business of イー╇ ウー╇ オー╇ even アーー people╇ once a month the financial director is going down to the bank with a check and he gets a suitcase full of cash and he comes back to the office and he hands out envelopes of cash to his staff.

Despite recent changes, modernity, on many levels, was not in the direct line of sight in mid- 2014. IFC consultant Julie Earne explained:

On the surface, you arrive here and you look around and it looks like a very modern city, Yangon �Myanmar‒s largest city and commercial hub『. And then you move outside of Yangon and you realize that this is an anomaly and most of the country is agrarian and not linked in and left behind..

Myanmar was also the last frontier for mobile telephones. In 2012 only an estimated 9%む12% of the people there owned a mobile phone, and fewer than 400,000 had Internet access.12 Part of the reason for this low penetration was cost; the scarcity of SIM cards was also a factor.v For example, in 2013 MPT made only about 350,000 SIM cards available, at a cost of 1,500 kyats (about $1.50), through a lottery system め but on the grey market those cards sold for 50 to 70 times that amount.

“s part of Myanmar‒s modernization effort, the government put out a telecommunications tender bid in early 2013. It was actually the world‒s most competitive licensing competition ever seen. There were 92 bidders right at the beginning. Two international firms, Ooredoo and Telenor, were selected.

One 2014 estimate suggested that telecoms could contribute as much as キ╆エゾ of Myanmar‒s GDP over a three-year period and employ as many as 66,000 people full time.

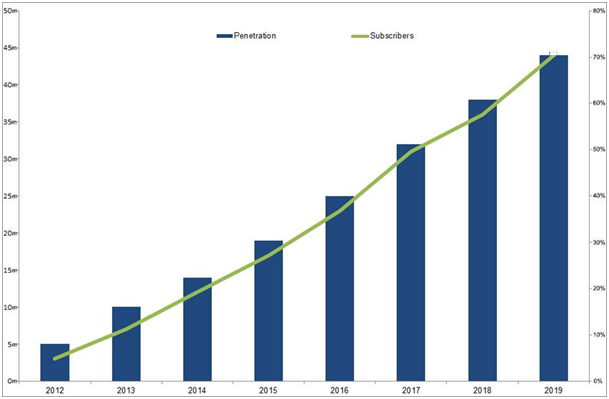

See Exhibit 2 for projected telecom subscribers in Myanmar, 2012む2019.

Looking for Financial Management Assignment Answers?

VIDEO EXCERPTS

Link 3: Earne on pace of cultural change Link

4: King on cash-based society

Link 5: Htun on challenges facing the rural population

The Company: Ooredoo Myanmar

Myanmar was slated to become Ooredoo‒s second-biggest market by population after Indonesia. Between operating expenses, capital expenses, and the 2014 portion of the license payment, Ooredoo estimated that it had invested $1 billion in Myanmar in 2014 alone.

Sensitive to the costs incurred╇ Ooredoo‒s business plan expected that the products and services launched in Myanamar would be profitable by year three, standard practice in the mobile telecom industry. The company saw one of its core competences as operating profitably in turbulent, high-risk environments.

Ooredoo had taken several steps to mitigate risk in Myanmar by working with the government to strengthen the legal framework, vi alleviating land issues, and exercising sensitivity in regions in conflict and hard-to-reach areas. It had also created direct ties in-country by hiring 800 local employees and by sponsoring the country‒s Football Federation and the national soccer team.

In the three months following the issuance of its license in February 2014, Ooredoo had begun to build out its network. It had contracted with a mandated tower construction company,15 built its first towers, completed the switch in Yangon, and made its first successful call.

Ooredoo rolled out its 3G services beginning in several major cities, with plans to quickly expand into rural areas. The network would require no further upgrades to accommodate mobile financial services.

It was expected that Myanmar‒s mobile phone system, like those of other emerging markets, would operate on an almost exclusively prepaid basis. SIM cards would be sold via a network of agents and dealers in convenience stores and other retail outlets throughout the country.

Ooredoo SIM cards were only compatible with phones with 3G service or higher め i.e., with smartphonesめwhich presented some challenges. As Jennifer Ong, a Bain consultant working in Myanmar, explained, it would be up to the agents who sold the cards to ⦆explain it to customers such that when they buy an Ooredoo SIM card they would check their phone and make sure it is compatible. Because if you put an Ooredoo SIM card in a phone that is not compatible with this network then their user experience is going to be quite terrible.を

Ooredoo had already signed contracts with the leading distributors and was on its way to achieving its five-year goal of 240,000 SIM activation points and approximately 722,000 top- up points of sales. Launching about one month prior to Telenor, Ooredoo sold over one million SIM cards the first week out of the gate╇ with Cormack observing╇ ⦆We‒ve got over a million customers╊ which we‒re obviously very pleased about╇ but also very humbled about because it‒s higher demand than we even expected╇ even knowing that there was huge pent-up demand.を

Ooredoo advertised its launch on huge billboards and incentivized early sign-ups with offers of free Internet access. Click here for promotional video leading up to launch. See Exhibit 3 for additional marketing collateral.

VIDEO EXCERPTS

Link 6: Cormack on winning the bid Link

7: Gorman on preparing for launch

Link 8: Cormack on the industry‒s inflection point

The Competition: Telenor Myanmar

The other major player awarded a license was the largest carrier in the Nordic region, the state- controlled Norwegian firm, Telenor. Telenor had over 150 million customers worldwide, with extensive operations in Asia, including in Myanmar‒s neighbors Thailand, India, and Bangladesh as well as in Malaysia and Pakistan. In Myanmar, Telenor hoped to replicate its customer experience in Pakistan, where its subscriber base had soared to an estimated 32 million over 10 years and where the company‒s Easypaisa mobile financial services had taken off.

Like Ooredoo, Telenor was running at full capacity on multiple fronts in Myanmar to identify potential distributors and cell phone tower sites, deal with operating challenges such as a chronic shortage of electricity, and obtain permission to build cell towers. Petter Furberg, Telenor‒s chief executive for Myanmar, noted that the services would roll out in three major cities just ahead of its planned November deadline:

An extensive distribution network will be the backbone of our mass market approach╆ “s part of Telenor Myanmar‒s network roll-out plan, we will recruit distributors and franchisees in each and every state and region in Myanmar with the goal of establishing a network of 100,000 retailers within five years of the network and service roll-out. These partners will include ⦆mom-and-popを shops and other small businesses╇ and will sell a wide range of Telenor‒s mobile communications products and services, such as SIM cards, recharge vouchers and other value-added services, at locations convenient to our customers.

Unlike Ooredoo, Telenor would offer 2G services in addition to 3G voice and data, with an additional deployment of services expected subsequent to launch. Telenor‒s SIM cards would therefore be compatible with inexpensive feature phones as well as smartphones. Telenor‒s stated launch strategy was to capture the market lead position with a low-cost operating model, a high degree of outsourcing, and a lean organizational structure. Customer pick-up was based on the continued decline in handset pricing, with feature phones priced from $10 and smartphones from $35.

According to most industry observers, Telenor would be a formidable competitor for Ooredoo. And, as Ong commented╇ ⦆On Telenor‒s side the advantage that they have is they are launching both a 2G and a 3G network. 2G is an older technology that all phones would be able to tap into, feature phones included, so anyone who wants to buy a Telenor SIM card can just buy it straight off and use it in their phone.を

Do You Need Same or Similar Assignment Answer for College & University Examination Requirement?

VIDEO EXCERPT

Link 9: Ong on Telenor and 3G versus 2G service

The Telecom Industry: Airtime

Mobile network operators (MNOs) generated revenue for airtime use either through exclusive contracts with customers or by charging for minutes added to a branded SIM card, and they closely monitored average revenue per user (ARPU) for the networks in which they operated. ARPU in Asia was around $60 per year. Profit margins industrywide averaged about 30%.

Customer retention rates, and the associated churn rates (or customer turnover rates) were also an important metric. As Gorman noted, Telco operators have had mixed results on becoming personal brands. Around the world╇ people who love “pple╇ love “pple╆ Doesn‒t matter what “pple does╇ they love “pple╆ Telecos haven‒t been as successful in having that passionate connection with their customers.

Gorman added that banks, too, typically engendered more loyalty from their customers than MNOs did. That said, in markets like the United States where customers tended to be locked into contracts and operators had loyalty programs, churn rates might be as low as 1.35% per month, or 15% a year.21 But churn was an especially important metric in emerging markets. As Ong explained, Developed markets are mostly a postpaid market so it is a lot easier there to drive customer loyalty because they are tied to a contract. In an emerging market where it is mostly prepaid, how do you drive customer loyalty when people can just buy your SIM and throw it away?

In prepaid markets, churn was typically defined as occurring when a customer did not use an MNO‒s branded SIM card for three months╉ in fact╇ most telecos deactivated a SIM card after three months. In India, with more than 15 mobile operators in a highly competitive, predominantly prepaid market, a study published in 2014 noted that the annual churn rate surpassed 50% (equivalent to a monthly rate of 6%). Competitive pressure, not surprisingly, also led to lower ARPU.

Customers in prepaid markets generally bought a SIM card with a limited number of minutes at the time of their phone purchase. As they used their phone, they replenished their stock of minutes through branded top-up scratch cards with unique codes, available from a wide variety of retail outlets.

John Nagle, CEO of a global cash-processing network, explained the top-up process:

A scratch card is airtime that a consumer buys from a retailer╊ so they go in and they ask for a top-up and what they‒re doing is they‒re loading valueめfive or ten or 20 dollars‒ worth of airtimeめonto their phone╊Mobile operators print a card with their brand on them and they print a number at the back and they put a foil over the number so that you can‒t read it. You scratch out this and you input the number and it puts the value of the card onto your airtime on your phone.

The agents selling these cards would buy them in a variety of denominations and typically sold several mobile operator card brands. Different mobile operators offered slightly different denominations and agents would be challenged to keep all of the brands in stock. Ooredoo cards, for example, would be offered in denominations of 5,000, 10,000, and 20,000 kyats. Based on a Myanmar usage study conducted in May 2013 (when MPT was the only mobile provider), customers tended to top up most frequently at local convenience stores (61%), followed by mobile stores (33%). About 88% of customers purchased top-up cards for five minutes or less.

Just as SIM cards connected customers to their voice service, agents were the mobile network operator‒s connection to its client base め not just to sell the products, but also to educate consumers about changes in service. Ooredoo had two levels of dealers: super dealers and dealers. The super dealers bought the airtime in bulk, recruited and organized the dealers, and resold the airtime to them. The dealers sold the airtime directly to Ooredoo‒s customers╆

VIDEO EXCERPTS

Link 10: Gorman on customer loyalty Link 11: King on churn

Link 12: Nagel on airtime top-ups

The Telecom Industry: Mobile Financial Services

Broadly defined, mobile financial services allowed customers (or agents working on their behalf) to conduct monetary transactions and pay for goods and services using the mobile phone as a platform. In 2013 there were 208 live mobile financial services operating in 83 countries, 60% of which had been launched in the past three years. Ooredoo was considering the launch of mobile financial services with a money transfer service (government regulations stated that transactions would be limited to 300,000 kyats per transaction), followed by other services such as bill payments.

There were two basic ways to deliver mobile money services to customers: one option was a mobile wallet, an e-account that customers handled directly, using their phone to transfer money from their account to other e-accounts or to agents. Over time, as additional services became available, the mobile wallet could allow customers to conduct a wide range of transactions, including money transfers, bill payments, the deposit of wages, and the purchase of goods or servicesめincluding airtime. The other delivery model was an OTC service, where payment and money transfers were processed by handing cash to an agent who transferred the money on the customer‒s behalf.25 This service did not require the customer sending money to have a mobile phone.

THE MOBILE WALLET MODEL

Many industry observers believed mobile wallet to be the endgame in mobile finance for the unbanked, providing that population a faster track to true financial inclusion. Most MNOs paid agents a commission for the cash-in/cash-out services they performed for money transfers, even when the customer used his or her own mobile wallet for the transaction.

Airtime could typically be bought directly from the MNO by a customer using a mobile wallet; the MNO paid no transaction fees to the agent for those purchases.

Financial inclusion experts believed that customers using mobile wallets gained more trust in the workings of formal financial systems and ultimately would upgrade from money transfers and bill payments to more sophisticated value-added services such as loans and savings accounts.

The launch of mobile wallet services often impacted new SIM card acquisition rates, with some operators reporting growth rates in their customer base increasing by approximately 3%. At the high end of customer-acquisition statistics accompanying mobile wallet launches, Telenor Pakistan reported a 14% increase in subscribers in one quarter of 2010 compared to the same period in 2009.26 SIM cards could be topped up from the mobile wallet, thus eliminating the period that customers were without airtime service, which could increase ARPU by as much as 15% because of increased use of that service. The experience of MTN Uganda was instructive in terms of potential synergies between the mobile wallet business and the airtime business. Launched in partnership with Stanbic Bank in March 2009, MTN Uganda‒s MobileMoney service enabled customers to send and receive money domestically and to buy airtime using their mobile phone. Customer churn decreased from 45% annually to less than 10% annually after MTN introduced mobile wallets.

M-Pesa

One of the best-known examples of a mobile wallet network serving the unbanked was M- Pesa. M-Pesa was launched in Kenya in early 2007 by Safaricom (part of the Vodafone group) as a mobile wallet service that allowed users to deposit, withdraw, and transfer money with a mobile device. All that was required to access M-Pesa was to go the nearest M-Pesa agent or outlet. After providing proof of identification, the customer opened a mobile wallet with his or her phone number and was given a four-digit PIN number. The PIN guaranteed that only the account owner could access the funds. To deposit money in their wallet or withdraw funds from it, customers went to an M-Pesa agent. To transfer money to another M-Pesa account, they entered their PIN and the amount to be sent on their phone, and the funds were instantly transferred to the receiver. Ordering a money transfer with M-Pesa felt a lot like sending a few SMS (text messages). If the SIM card was lost, the customer brought proof of identity to an M- Pesa branch to get a new card with the same phone number and the same account information.

Within eight months of M-Pesa‒s launch, over 1.1 million users had transferred a total of over 87 million USD using the service; by September 2009 over 8.5 million users had transferred a total of 3.7 billion USD. By June 2014 M-Pesa had 15 million users conducting more than two million daily transactions.

At the time of launch, Kenya had an almost 40% penetration of mobile phones, in which Safaricom was the clear market share leader, with 80% of the customer base. Nearly 20% of Kenyans were unbanked. One year after launch, one study estimated that over 80% of Kenyans were aware of M-Pesa, and 66% had used it.

At launch, Kenya had a very limited financial infrastructure in place with only 491 branch banks, 500 post office branches, and 352 ATMs servicing a population of 15 million. Within a year after launch, M-Pesa had 2,262 distribution outlets; by March 2009 this number had risen to nearly 10,000.

However, despite the high penetration of mobile phones in Kenya and other factors such as a Central Bank regulation supportive of mobile financial services, the service was not profitable until year three.

THE OTC MODEL

With OTC services, customers went to an agent who performed the transaction on their behalf, using his or her mobile phone to send the funds to the recipient‒s phone╆ The sending customer paid the agent in cash for the amount to be transferred and needed neither a SIM card nor a phone. An SMS with an access code for the money was then sent to the recipient, who went to another agent who ⦆cashed outを the funds (less a stated fee). In this model, the agent served a similar function as a private bank め the predominant channel for money transfers where no mobile money system existed め at locations that were presumably more convenient for customers.

Ong described the benefits to launching an OTC service in a developing market:

The advantage of an over-the-counter model is that it is easier to educate people about mobile money through it. With mobile money you are basically telling someone to use their phone to perform financial transactions. But you need to assure people of the security of the transaction, right? So when you use an OTC model, you have the agent who will explain how this is going to be done and you have the agent doing it as well.

According to King, OTC service had some distinct advantages over the mobile wallet, especially in the short-term╈ ⦆The benefit with OTC is the immediate volume that you get╆ That‒s not necessarily a benefit for us, but it‒s a benefit for our agent network because if you don‒t give your agent network enough volume╇ they‒re going to lose interest╇ simple as that╆を Given that Ooredoo had just launched airtime services, the use of the OTC network to launch mobile money meant that the company did not need to wait for penetration of Ooredoo SIM cards into the market to gain momentum. (Mobile wallets, on the other hand, relied on customers buying Ooredoo SIM cards to use in their own phones to make money transfers.)

Easypaisa

One of the best-known examples of an OTC model was Telenor‒s Easypaisa service in Pakistan. When Telenor Pakistan and Tameer Microfinance Bank launched Easypaisa in 2009, 88% of the population in Pakistan did not have access to formal financial services, with only 2,500 banking branches servicing 105 million people in the rural areas of the country. However, there was 65% mobile penetration (a figure that was projected to grow to 95% by 2013), creating what industry observers termed ⦆a perfect storm of factors that had the potential for the explosive mobile financial services adoption: a proactive mobile operator, an operator with a banking license and a market with high mobile penetration but low financial inclusion.を

Easypaisa was lauded by financial inclusion organizations as an overwhelming success:

They created a network of over 11,000 agents, each processing bill payments and money transfers. Easypaisa is unique in that customers do not need to have a mobile account with Telenor to pay their bill at an Easypaisa shop め they simply present their cash and bill to an agent who completes the payment on a mobile phone.

Easypaisa had also delivered huge benefits to Telenor Pakistan, having proven to be a customer acquisition tool. See Exhibit 4 for screenshot from the site.

In 2013 the Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP) reported that Easypaisa was the third-largest mobile money deployment in the world, serving 7.4 million unique users. Of these customers, 2.4 million were wallet users and another 5 million were unique OTC customers.

OTC service was originally conceived as a bridge for the unbanked to mobile wallets and ultimately to more sophisticated financial instruments, but Telenor reported that this migration had been slow:

We have to recognize that OTC is a real solution for a particular segment of the unbanked and is there to stay. Regardless of how convenient and attractive we make mobile wallets, there will always be a segment of customers who will prefer the OTC solution because they find it easier to rely on the agent to send money and they prefer not to open an account for themselves.

As industry watchdog service GSMAviii reported╈ ⦆[OTC] agents are at the frontline of every mobile money deployment╈ if they don‒t sign up customers╇ no customers sign up╉ if they don‒t hold float,ix customers can‒t transact╉ and if they aren‒t reliable╇ the mobile money service won‒t be seen as reliable╆を

Much more was required from mobile money agents than from agents selling prepaid airtime, who only stocked and sold SIM and top-up cards. Mobile money agents needed to be better capitalized. Research had shown that they needed up to ten times more float than their airtime counterparts required and that they waited longer for their profits. Regulations in most countries also required that mobile money agents have a bank account.

In addition, mobile money agents also needed more training, and their work was more labor intensive. The sale of airtime simply involved selling a scratch card, whereas the sale of a money transfer required handling the transaction, educating customers, and helping them through the process. Whenever a customer came to an agent to send or receive money, or a client with a mobile wallet came to an agent for cash-in or cash-out services, the agent would receive a commission. SIM card sales and top-ups generated higher margins per transaction and quicker payouts for agents than money transfers or bill payments did, so the agent incentive scheme for mobile money needed to be carefully crafted.

Ong explained that there was a trade-off for patient agents:

With OTC, agents can earn a commission from the money transfer itselfめ whereas with a wallet system, they only earn commissions from the cash-in and cash-out. So how do you continue incentivizing these agents? You promise them increased volume and then you find other ways to incentivize them. For instance, you give them an incentive for getting people signed up to a wallet. Or for every customer they register, they get a cut for every mobile money transaction the customer performs (up to a certain number).

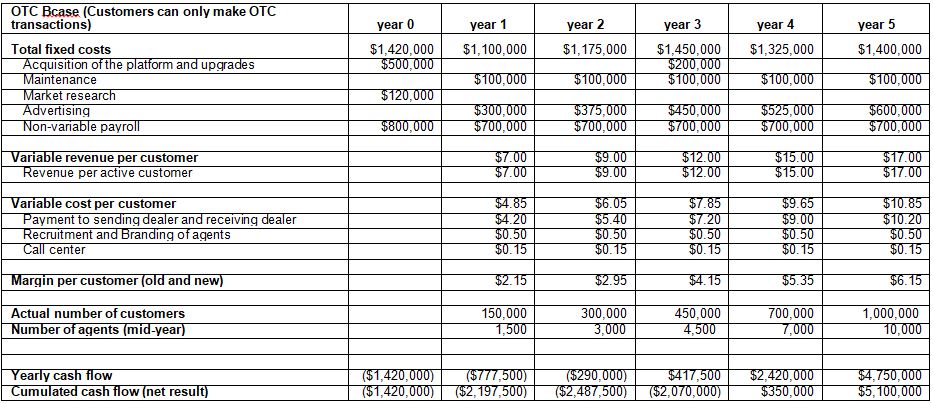

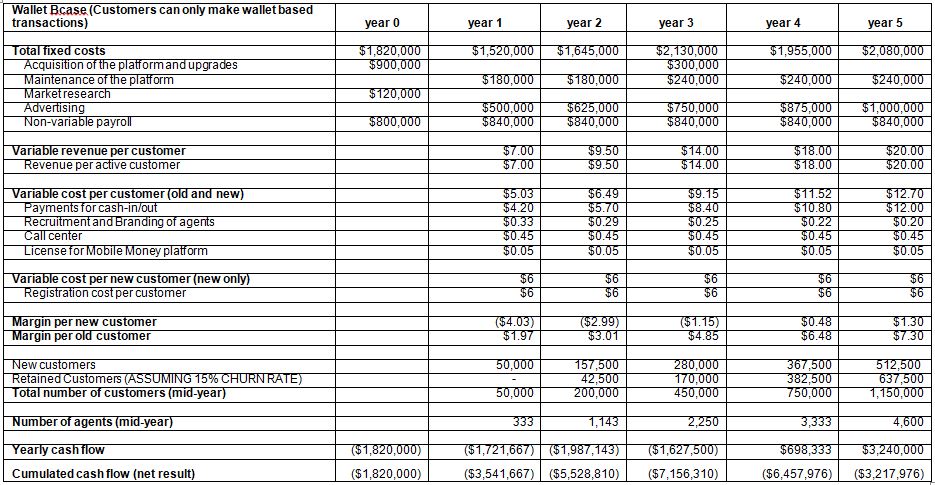

THE ECONOMICS OF MOBILE WALLET VS. OTC MODELSx

Based on industry norms, the revenues and gross margins earned from consumer fees for money transfer services were almost identical for mobile wallet and OTC. In the case of the wallet, for each transactionめregardless of the amountめthe sender would pay a $0.05 personむto-person transfer fee, and the receiver would pay $0.70 for cashing out (withdrawing) the money from an agent. The telecom company would pay a commission of $0.225 to the agent who made the deposit on the sender‒s wallet �i.e., provided cash-in service) as well as a commission of ┵ー╆イイオ to the agent who made the withdrawal from the receiver‒s wallet (i.e., provided cash-out service). In other words, the telecom company would pay 60% of the customer‒s fees as commissions to the agents and would retain 40%.

In the case of OTC money transfers, the sender would pay the fee of $0.75 (about 770 kyats) per transaction to the telecom company, and the telecom company would then pay commissions of $0.225 to the sending agent and $0.225 to the receiving agent. Again, the telecom company would retain 40% of the customer‒s fees.

Although the revenues and gross profits per money transfer transaction were similar in the OTC and mobile wallet cases, the number of money transfer transactions was expected to be greater in the mobile wallet model because of ease of use. On the other hand, initially the adoption of mobile money transfer was expected to be faster for OTC than for mobile wallet, for several reasons: senders and receivers would not need a SIM card to complete the transaction; less customer education would be required; and agents would likely be incentivized to promote the money transfer service. However, as the number of services offered by the mobile wallet (e.g., bill payment and direct deposit of salaries) increased, in later years the number of customers was likely to grow faster with a wallet compared to OTC.

Despite these advantages, because the wallet was a more sophisticated system, in offering it the telecom company would incur additional expenses: costs to develop and maintain the technology platform, higher marketing and salary expenditures, and registration fees paid by the telecom company to the dealer each time they registered a customer.

These financials are captured in Appendix 2.

VIDEO EXCERPTS

Link 13: King on role of banks and mobile money providers

Link アエ╈ Paing on the banks‒ interest in mobile money Link

15: Htun on serving the rural unbanked

Link 16: Ong, King and Paing on OTC versus mobile wallet

The Customer for Mobile Money

Wanting to better understand customer needs relating to mobile money services in Myanmar, Ooredoo commissioned qualitative and quantitative market research in the spring of 2014. See Exhibit 5 for a screenshot of the female participants.

General findings confirmed market observations. Most people in Myanmar were in need of cash transfer services but lacked the infrastructure for the transactions. Money was primarily sent to and from the Yangon and Mandalay areas. Transfers were currently done using a private or government bank, bus service personnel, friends and relatives, or Hundi (a trust- based informal network of money transfer intermediaries); private banks were the most common channel. Banks were used primarily by salaried workers in urban areas to transfer money to relatives in rural areas. A bank account was not necessary to make use of this service, but with branches few and far between, access was difficult for the roughly 75ゾ of Myanmar‒s population who were agrarian and lived in more remote areas. Pwint Htun, a native of rural Myanmar who is now a CGAP consultant to the World Bank, shared this insight:

I was talking with a farmer and she said every time her daughter sends her remittance back from Thailand, she needs to go to the nearest town and withdraw the money. She has to wait in line at the bank, sometimes wait for the bank staff to have lunchめit‒s half a day of work for her just to collect the payment╆

The process of money transfer at a bank took about 30 minutes on average, from the time spent in travel to completion of the transfer. There were a limited number of bank branches and bank operating hours were inconvenient. Attributes that were considered important in money transfer services were speed of the transaction and convenience, costs, security, and ease of use.

Gorman considered how a typical customer might think about switching from using a bank‒s money transfer services to using mobile money transfer services. Would the customer benefit economically? In terms of pricing, a leading bank charged $0.49 (about 500 kyats) for the fax fee plus 0.15% of the amount being sent. There were no set charges associated with Hundi, bus terminal personnel, or friends (these services were typically provided in exchange for favors or other services) but め especially with Hundi or the bus service personnel め there was less certainty that the money would actually arrive. In terms of customer understanding, a fixed fee per transaction would be the easiest for the Myanmar market to understand.

VIDEO EXCERPTS

Link 17: Liew on current money transfer process at banks

Link 18: Tan on key research findings

Ooredoo’s Proposed Launch Plan for Mobile Money

Based on the market research findings, Gorman thought that the first mobile money service Ooredoo should launch was money transfer, with mobile bill payment as the next likely service to roll out.

Unlike M-Pesa agents in Kenya, telecom operators in Myanmar were required to partner with a bank licensed by the Central Bank to offer mobile money services. This presumably provided benefits to consumers of telecom financial services (in the form of regulated security for their money) and most definitely to the banks, which benefitted from the associated float. After considering several partners, Ooredoo selected CB Bank. King described how float would work for the bank:

The way that mobile money works is that an agent goes to our bank, our partner bank, and deposits money in their account. We then receive notification from the bank that that money has been deposited for that agent and we credit or issue mobile money to that person…What that means is that at any given time there is always cash in the bank account backing up the money that happens to be floating around the system at any given time. That money sitting in that bank account is referred to as the float. That float can be massive. Absolutely massive…I think the return here [in Myanmar] that the bank would get would be about 13%. If you consider the fact that we may well have in the region of 50 or 60 million dollars on deposit at any given time, that‒s a nice return for the banks.

All Ooredoo mobile money agents would be required to have a CB bank account, although the account requirements would be limited to approved identification and an address. Balances would be limited to one million kyats. CB Bank would be responsible for compliance with regulations as defined by the Central Bank. For its part, CB Bank would earn interest on the mobile money float and, with the future launch of additional financial services, presumably be able provide debit cards, micro loans, savings accounts, and micro insurance to Ooredoo‒s customers.

With airtime agents and dealers already in place, Gorman considered how to develop a network of mobile money agents to both sell its products and educate consumers about the use of those products. The options he considered were to leverage Ooredoo‒s existing airtime agent network, to create a separate network of agents who exclusively sold mobile money products, or to engage a third party to distribute mobile money products. The decision was complicated by the fact that as customers began to make airtime purchases over their phones, moving to a mobile wallet would likely, over time, diminish the immediate commissions agents made on airtime sales. But for the foreseeable future, agents would be the face of the brand and were essential for consumer education.

As Gorman noted, ⦆The thing you have to consider is having a viable commercial model for the agents. If the money turning over in the system can only sustain a certain number of agents, you know you need a certain amount of revenue and a certain number of transactions to keep them interested and busy╆を

WEIGHING THE OPTIONS

Gorman was still undecided about whether to roll out Ooredoo‒s money transfer service in Myanmar with OTC or with a mobile wallet. In thinking of OTC money transfers, one extreme option would be that the sender and the receiver would not be required to use an Ooredoo SIM card. The agents would complete the transactions on behalf of the customers. Gorman considered the implications of the mobile wallet model for the central airtime business. Though it was difficult to estimate the airtime “RPU in Myanmar due to the country‒s low mobile penetration prelaunch, Ooredoo estimated an ARPU of approximately $5.00 per month.34 With increased competition and cellphone penetration the ARPU was expected to decline. This would not change with the launch of mobile financial services using the OTC model. However, if a mobile wallet system were launched, industry analysts estimated that ARPU would increase by 15% because of the ease of topping up the SIM card using the wallet; customers might increase phone usage, and hence, the ARPU could go up accordingly. This increase in ARPU was significant, given that net profit in the airtime business was in the range of 30%. Ooredoo could also expect the churn rate of its mobile wallet users to lower to an annual rate of 15%; a 50% annual churn rate was expected to apply to the rest of the customer base. This was a conservative estimate, based on the experience of MTN mobile money Uganda め where the churn rate dropped to as low as 3% among mobile wallet holders. (The reason for the lower churn rate among mobile money users was the high degree of consumer stickiness to bank services relative to mobile carriers.)

There were also other synergies to consider. When customers used their wallet to buy airtime, mobile telecoms would not need to pay the 8% commissionxi to the dealers for top-ups. Finally, Gorman believed that by offering a value-added service such as a mobile wallet, Ooredoo could compete better against Telenor and increase customer acquisition. The actual increase was not quantified, although speculations ranged from a growth of 3% to 5%.

On the surface, Myanmar was a textbook opportunity for mobile money, as Gorman pointed out╈ ⦆[There is a] very large╇ unbanked population╊╆The mobile networks are just rolling out now. The technology is much cheaper than it was ten years ago╆ So you‒d think that all the ingredients are in place for mobile money to be successful here. を Yet, as Gorman also noted, most of the people in Myanmar would be experiencing a cell phone for the first time, and asking them to understand mobile financial services so soon might be a risk because ⦆there‒s only so much people can absorb quickly.を

King and Gorman were both aware of the unique challenges this ⦆last frontierを presented. Gorman summed up the task before them:

The difficulty with mobile money is, of about the 220 odd deployments around the world╇ there‒s some common characteristics among the successful ones╊even then ten or twenty are actually profitable. But the consistency is about scale, operator lead, and the regulatory environment.

With Telenor days away from launching airtime services, Gorman carefully considered Ooredoo‒s next steps. Was Myanmar truly ready for mobile money? If so, what should the timing of the launch plan be? And once launched, what should the model look like?

VIDEO EXCERPTS

Link 19: King on bank float

Link 20: Liew on benefits of mobile money

Link 21: King final thoughts

Link 22: Gorman final thoughts

Exhibits

Exhibit 1

Myanmar Consumer Overview

| Demographics | |

| Male | 46% |

| Female | 54% |

| Urban | 23% |

| Metropolitan | 10% |

| Rural | 67% |

| Life expectancy (male) | 61 years |

| Life expectancy (female) | 67 years |

| Literacy rate | 92% in 2009 |

| High school | 54% |

| Secondary education | 11% |

| Avg # of children | 2.03 |

| Avg. urban household size | 4.2 |

| # Generations under one roof | 2 (69% of households) |

| Occupation | |

| Self-employed | 65% |

| State-owned business | 17% |

| Private—local | 15% |

| Private—foreign owned | 1% |

| NGO | .2 |

| Income | |

| Less than $188US per month | 54% |

| $189-$375 per month | 14% |

| $376-$625 per month | 6% |

| None | 23% |

| Urban income classification | |

| High socio/economic>$500/month | 22% |

| Middle socio/economic $225-500/month | 36% |

| Low socio/economic <$225/month | 42% |

| Household amenities | |

| CRT TV | 73% |

| Rice cooker | 77% |

| Refrigerator | 60% |

| Indoor plumbing | 40% |

| Air conditioner | 19% |

| Plasma TV | 18% |

| Washing machine | 17% |

| Gas stove | 12% |

| Internet | 2% |

| Wish list | |

| Washing machine | 21% |

| Refrigerator | 15% |

| Laptop | 15% |

| Air conditioner | 14% |

| LCD/Plasma TV | 13% |

| Mobile phone (not smartphone) | 12% |

| Tablet (i.e., iPad) | 8% |

| Digital camera | 8% |

| Personal computer/desktop | 7% |

| Smartphone | 7% |

Exhibit 2

Projected Telecom Subscribers in Myanmar, 2012–2019

Exhibit 3

Ooredoo Airtime Services: Marketing Launch Collateral

Exhibit 3 (continued)

Exhibit 4

Easypaisa Site Visual for Mobile Money Transfer

Exhibit 5

Focus Group Participants

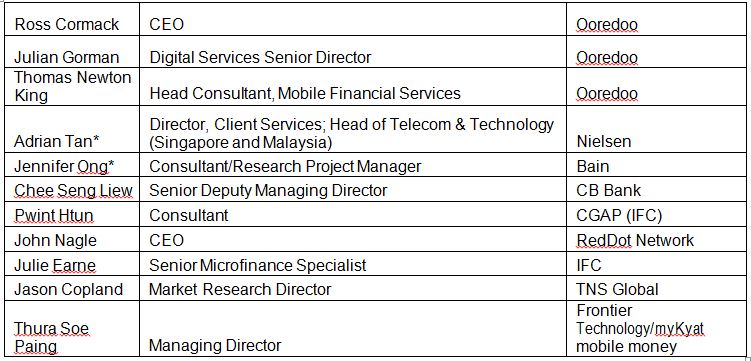

Appendix 1

Case Participants: Interviewee List in Yangon, Myanmar

Appendix 2

Base Case Projections (Case Writer Estimates)

Appendix 2 (continued)

Base Case Projections (Case Writer Estimates)

MOBILE WALLET

End notes

1 Daniel Ten Kate╇ Kyaw Thu╇ and “dam Ewing╇ ⦆Myanmar Picks Telenor and Ooredoo for Phone Licenses, を BloombergBusiness, June 28, 2013, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-06-27/myanmar-picks-telenor-and-ooredoo-for-phone-licenses-over-soros. (Note: penetration numbers vary from 8% to 12%.)

2 をTelenor and Ooredoo Win Myanmar Telecoms Tender╇を DW, June 27, 2013, http://www.dw.de/telenor-and-ooredoo-win-myanmar-telecoms-tender/a-16911779..

3 “ung HlaTun and Jared Ferrie╇ ⦆Update 3 む Telenor, Oordeoo Win Myanmar Telecoms Licenses, を Reuters, June 27, 2013, http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/06/27/myanmar- telecoms-idUSL3N0F312M20130627.

4 Jeffrey Riecke╇ ⦆Inclusive “ctivity in Myanmar╇を Center for Financial Inclusion Blog, June 10, 2013, http://cfi-blog.org/2013/06/10/inclusive-activity-in-myanmar/.

5 All statements by Mr. King (head consultant, mobile financial services, Ooredoo Myanmar) are cited from August 28, 2014, interview in Yangon, Myanmar. (See Appendix 1 for case interviewee list.)

6 ⦆Myanmar╇を The World ”ank╇ http://data.worldbank.org/country/myanmar.

7 CI“╇ ⦆GDP �Official Exchange Rate�╇を The World Factbook,

https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2195.html#bm.

8 ⦆World Development Indicators╈ Education Completion and Outcomes╇を The World ”ank╇2014, http://wdi.worldbank.org/table/2.13.

9 Cited from September 2, 2014, interview in Yangon, Myanmar.

10 ⦆Twinned with South Sudan╇ を Economist, October 25, 2014, http://www.economist.com/news/finance-and-economics/21627698-myanmar-has-licensed- few-foreign-banks-its-financial-sector-still.

11 Cited from September 1, 2014 interview in Yangon, Myanmar.

12 ⦆Chairman‒s Message╇を Ooredoo Annual Report 2013, 6.

13 “ngelina Draper╇ ⦆Tech Scene in Myanmar Hinges on Cellphone Grid,を New York Times, July 13, 2004, http://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/14/business/international/tech-scene-in-myanmar-hinges-on-cellphone-grid.html.

14 Draper, ⦆Tech Scene in Myanmar╆を

15 Two tower construction companies had been mandated: Myanmar Tower Company and Pan Asia Majestic Eagle╆ �Sources╈ ⦆Pan “sia Majestic Eagle Limited �P“MEL� Enters into First Ever Non-Recourse╇ Cross ”order Financing in Myanmar╇を Reuters, September 30, 2014,

http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/10/01/pamel-myanmar- idUSnPn5vlc2W+81+PRN20141001; ⦆Digicel Group and YSH Finance Sign “greement with Ooredoo Myanmar╇を Digicel Group╇ December イ╇ イーアウ╇ http://www.digicelgroup.com/en/media-center/press-releases/achievements/digicel-group-and-ysh-finance-sign-agreement-with-ooredoo-myanmar.)

16 All statements by Ms. Ong (consultant and research project manager, Bain Consulting Singapore), are cited from August 27, 2014, interview in Singapore.

17 Cited from September 2, 2014, interview in Yangon, Myanmar.

18 Khine Kyaw╇ ⦆Telenor‒s “im Remains High in Myanmar╇を Myanmar Eleven, August 22, 2014.

19 Telenor, presentation at analyst and press conference, February 10, 2014.

20 All statements be Mr. Gorman (digital services senior director, Ooredoo Myanmar) are cited from September 2, 2014, interview in Yangon, Myanmar.

21 Average monthly churn rate for Verizon, 2013, Q1╆ Source╈ ⦆“verage Monthly Churn Rate for Wireless Carriers in the United States from アst Quarter イーアウ to ウrd Quarter イーアエ╇を Statista, http://www.statista.com/statistics/283511/average-monthly-churn-rate-top-wireless-carriers-us/.

22 P. S. Rajeswari and P. Ravilochanah, ⦆Churn Analytics on Indian Prepaid Mobile Services,をAsian Social Science 10, no. 13 (2014 ccsenet.org/journal/index.php/ass/article/download/38130/21272.

23 Cited from September 1, 2014, interview in Yangon, Myanmar.

24 ⦆Usage and Attitude Study of Telecommunications Sector in Myanmar,を Business Insight, May 2013.

25 Greg Chen╇ ⦆Mobile Money╈ OTC versus Wallets╇を CGAP Blog, September 12, 2013, www.cgap.org/blog/mobile-money-otc-versus-wallets.

26 Telenor Pakistan む Scaling to Meet Accelerated Growth: Case Study: Telenor Easypaisa (Cape Town, South Africa: Fundamo), http://www.fundamo.com/PDF/Case%20study/Telenor%20Easypaisa%20Pakistan%20Case% 20Study.pdf.

27 GSMA Annual Report, 2009.

28 Telenor Pakistan む Scaling to Meet Accelerated Growth, 3.

29 ⦆MMU Examples む easypaisa╇を GSM“╇

http://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/programmes/mobile-money-for-the-

unbanked/mmu-examples/easypaisa.

30 Nadeem Hussain╇ ⦆The �EasyPaisa‒ Journey from OTC to Wallets in Pakistan╇を CG“P╇ October 10, 2013, http://www.cgap.org/blog/%E2%80%9Ceasypaisa%E2%80%9D-journey- otc-wallets-pakistan.

31 Hussain, ⦆The �EasyPaisa‒ Journey╆を

32 Neil Davidson and Paul Leishman, ⦆Incentivising a Network of Mobile Money Agents,を in

Building, Incentivising and Managing a Network of Mobile Money Agents: A Handbook for Mobile

Network (London, England: GSMA,April 15, 2010), 1.

33 Cited from August 30, 2014, interview in Yangon, Myanmar.

34 Ooredoo Group, Capital Markets Day 2014 (Doha, Qatar: Ooredoo, May 12, 2014), http://www.ooredoo.com/en/media/get/20140512_CMD-2014-Ooredoo-Myanmar.pdf.